My main area of specialization is analytic metaphysics, in which metaphysical problems are studied by the various methods of analytic philosophy that are used in contemporary philosophy (which is most prevalent in English-speaking countries).

Analytic philosophy is a quite general term that has been historically used, and there is not necessarily a clear, unified methodology. In general, however, the field can be characterized by the process where researchers present their answers to philosophical problems using relatively normal logical arguments and improve the accuracy and generality of their arguments through debates with other researchers who have opposing views. There are various approaches in analytic metaphysics. I use, among other things, methods of formalization based on modern logic and I study the question of what the nature of reality is (or can be) in general, centering on ontological category theory. This concerns—at the most general and basic level—the question of what kinds of entities, with what kinds of mutual relationships, exist (or can exist) in this world.

Be surprised

Aristotle said philosophy begins with wonder. Conversely, without wonder, philosophical thoughts would not arise. Wonder is often unique in that it can be a feeling of surprise toward the unquestioned and ordinary—things that have slipped our mind because they seem self-evident—or toward things that would usually not surprise anyone.

Clarify the surprise as a philosophical question

When embarking on a philosophical investigation, we sometimes do not clearly understand what on earth we are questioning. Also, philosophical confusion may be found in the question itself. It is therefore necessary to clarify the question and properly formulate it.

Discover the central issue

We ascertain the root of the problem and the main points of our answer by fully utilizing all sorts of means. These include removing confusion, impurities, vagueness, and ambiguities, exposing hidden premises, unearthing flaws in proofs (begging the question, vicious circles, contradiction, etc.), performing classification, analysis, and synthesis, and using analogy and thought experiments, in dealing with matters related to the question.

Generalize the central issue discovered

An important characteristic of philosophy (and metaphysics in particular) is investigation of problems at the highest possible level of generality. Beneath the surface of each specific philosophical problem, the problem is related to a class of more general problems in the same subject area and to problems in closely related areas. We pursue the root, essence, truth, and nature of reality in general by deepening our investigation with consideration given to such relationships.

Deepen our understanding

Even if we investigate a phenomenon from various angles, in most cases we will end up merely reconfirming its obviousness—a situation that can be described by the proverb “the mountain was in labor and brought forth a mouse.” However, we would have a deeper understanding of how it is obvious. In philosophy, the process of examining a problem is more important than the result. If we can make the “mountain” rumble with a “mouse,” we should be proud of it.

Let me give an example of philosophical investigation, using the problem called the mystery of mirror image reversal. This is discussed in the latter half of my book, Why Can’t We Go to the Past: A True Introduction to Philosophy. The problem cannot necessarily be considered typical in metaphysics, but it is appropriate for demonstrating the process of analytic philosophical investigation in a straightforward manner.

Let me give an example of philosophical investigation, using the problem called the mystery of mirror image reversal. This is discussed in the latter half of my book, Why Can’t We Go to the Past: A True Introduction to Philosophy. The problem cannot necessarily be considered typical in metaphysics, but it is appropriate for demonstrating the process of analytic philosophical investigation in a straightforward manner.

1. Be surprised

The mystery of mirror image reversal refers to the problem that only a left-right reversal occurs in the mirror, without an up-down reversal. This is an ordinary matter that we would naturally understand when we look into a mirror in daily life. But the fact that we see an object reflected in a mirror is the result of the purely physical phenomenon where light is reflected on the surface of the mirror. The phenomenon should then apply to light from any direction whose reflection is perceived by a person in front of a mirror. Yet, why does mirror image show only a left-right reversal but no up-down reversal? It seems as if some surprising phenomenon were occurring, with a degree of surprise that would be elicited by a statement like “The surface temperature of a mirror rises if light is projected onto it from horizontal angles, but does not rise for some reason if light is projected from vertical angles.”

2. Clarify the surprise as a philosophical question

What exactly is meant by the statement that only a left-right reversal occurs in the mirror, without an up-down reversal? Let us consider the following example. Suppose that you lie in front of a mirror with the left side of your body touching the floor. If you wave your right hand, which is above your body, the image of you in the mirror waves its left hand, which is also above its body. Therefore, in this case, an up-down reversal occurs, too (vertically with respect to the floor). What we notice here is that an up-down reversal can mean not only a reversal in the vertical direction (which is absolute for practical purposes and coincides with the plumb line), but also a reversal in the head-foot direction, which is relative to a body. The up-down reversal in the mystery of mirror image reversal refers to the latter. The question is thus reformulated as follows: Even though the head-foot direction and the left-right direction are both relative to the orientation of the object being considered, why does only a left-right reversal occurs in the mirror, without a head-foot reversal?

3. Discover the central issue

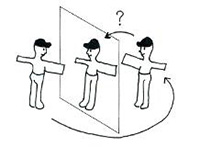

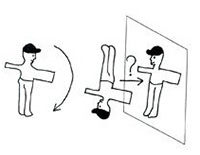

Suppose that you are wearing a shirt, and that the right sleeve is looser than the left sleeve. You want to compare yourself and your reflection in the mirror, so you imagine turning your body 180 degrees (Figure 1). You then compare your reflection in the mirror and the imagined self, which are both facing the same direction. You now notice that the side of the looser sleeve is different between the two. This is why we think that a left-right reversal occurs for an image in a mirror. However, there are actually a countless number of ways for you to imagine turning yourself before comparing your reflection in the mirror and the imagined self, both facing the same direction. For example, if you imagine turning yourself vertically (Figure 2), the orientation of the head (or feet) becomes different, unlike in the previous case. Therefore, the direction of reversal depends on the rotational axis used in comparing yourself and your reflection. The mystery of mirror image reversal arises from the fact that we unconsciously set such a rotational axis in the head-foot orientation and falsely believes that there would be no other way to perform a rotation.

Figure 1:

Comparison after a horizontal rotation

Figure 2:

Comparison after a vertical rotation

4. Generalize the central issue discovered

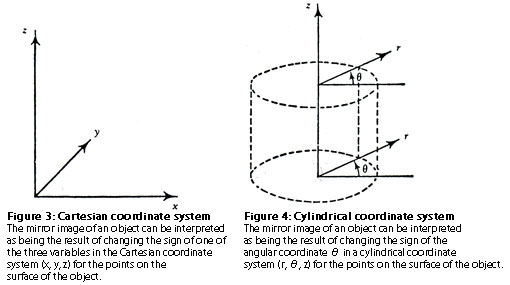

In his book, The Ambidextrous Universe, Martin Gardner generalizes mirror image reversal using the Cartesian coordinate system and argues, based on rigorous mathematics, that the mirror gives rise to a front-back reversal, instead of a left-right reversal (Figure 3). He also asserts that we perceive a left-right reversal because objects, including our bodies, are roughly symmetric and because we are captives of everyday language. However, if we generalize the phenomenon using a cylindrical coordinate system around the rotational axis (Figure 4), a left-right reversal can be interpreted, based on rigorous mathematics, as an operation in which clockwise positioning of an object is converted to counterclockwise positioning, and vice versa. In other words, Gardner’s view is just one of many interpretations of the reversal phenomenon. The left-right reversal is a mathematically interpretable phenomenon. Also, we normally perceive a left-right reversal but not a top-down reversal when we see the mirror image of objects, such as a desk lamp as illustrated in Figure 5, that are not left-right symmetric. We also see this in the letters “C” and “E,” which are symmetric in the vertical (head-foot) direction. We can therefore consider that the most important determinant of the orientation of the rotational axis in a left-right reversal is not the left-right symmetry of objects but gravity, which normally acts on objects in the up-down direction.

Figure 5: Desk lamp

5. Deepen our understanding

We normally interpret the mirror image of an object as being the result of a left-right reversal, using the concept of rotation. Put differently, our interpretation is based on a cylindrical coordinate system, rather than the Cartesian coordinate system. One reason is that we live in the Earth’s environment, taking the direction of gravity as a given special orientation, and this is unconsciously reflected in the act of looking in the mirror—a very routine activity related to our ability to recognize things. Through the mystery of image reversal, the mirror reminds us of our Earth-bound existence and teaches us the importance of an obvious, everyday thing like gravity, which exists as an absolute precondition, usually without being noticed.

Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences (Department of Philosophy and Art Studies)

Professor, Specialization in Philosophy

© Copyright Saitama University, All Rights Reserved.